contents

Unfolding Connemara and Elsewhere: a book and its whereabouts

Reading the Book

‘Echolalia’ / ‘The print of nature’

'Hexagon'

‘Déjà vu’

Conclusion

1. Unfolding Connemara and Elsewhere: a book and its whereabouts

Nicolas Fève

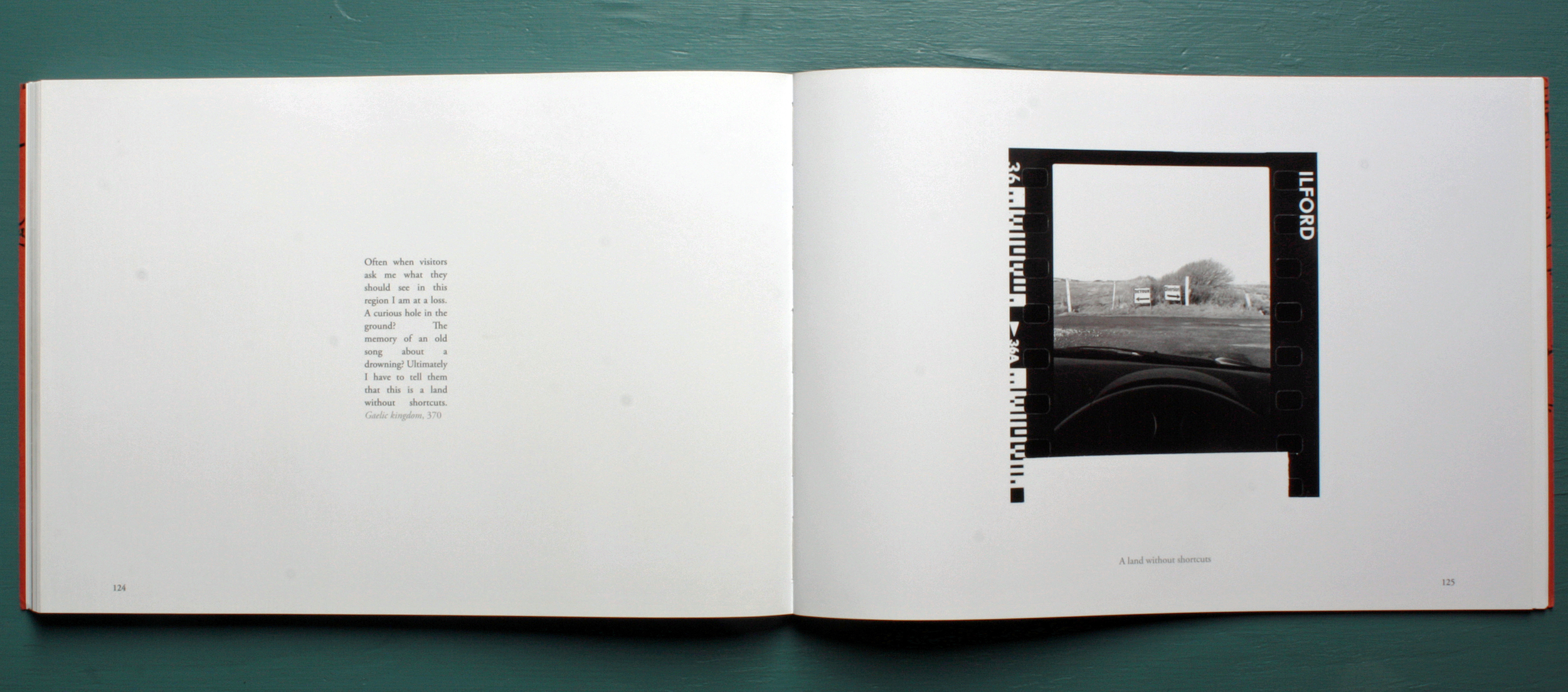

Between John Elder’s introduction which opens Connemara and Elsewhere (2014) and Tim Robinson’s three evocations of new elsewheres which close the volume, lies a photographic essay entitled ‘Browsing Connemara’. Juxtaposing 77 photographs with an anthology of extracts from Robinson’s writings, its aim is to provide a visual reading of Robinson’s Connemara and to explore the very idea of landscape. It also sets out, more generally, to present a conceptualisation of what Robinson terms ‘geophany’, namely the showing forth of the earth.

As I have outlined elsewhere, my own approach to Connemara coincides in many ways with Tim Robinson’s, despite the difference in the media we use. Photography, as I practice it in this very same place, leads to a questioning of the traditional understanding of landscape inherited from the end of the Middle Ages, namely the idea of it as a portion of land, a part of a greater whole, seen by a subject from a certain viewpoint. The aim of this short article is to examine, through the explication of a number of examples from ‘Browsing Connemara’, how that photographic essay presents an understanding of landscape which differs from the traditional one. Central to the project is an exploration of the idea of imprint and surface, including the imprint of people and their economy on landscape, and the imprint of the elements on people and their environment. Key also is a displacement in the images of the customary landscape perspective onto a kind of reading of the photograph in which the gaze is destabilised, or onto the interplay between text and image. Landscape raises questions of space and gaze, angle and distance, and hence the broader question of dimension. Within the context of this photographic essay, and indeed the overall project of the photo-book, the dimension at play is that of the book.

2. Reading the book

A word on the form of the book may be useful to start, and the ways in which it aims in its very materiality to evoke the ‘topographical sensations’ to which Robinson refers. Firstly, the soft cover makes the book floppy, unstable, causing the book to undulate the way the Connemara landscape undulates, rising and falling unexpectedly. It provokes a certain sense of discomfort for the reader in its instability, mirroring the instability the walker feels as he sets out across a boggy Connemara plain. The handling of the book is felt. Secondly, the play with format is key, in the case of both the landscape format of the book, and the interplay of landscape and portrait formats on the level of the page. This play with format is central to the conceptualisation of the volume as the portrait of a landscape, a montage around a spine which calls to be folded and unfolded. When the volume is opened up, is unfolded so to speak, the double-page spread of two A4 pages with which the reader is faced evokes a panorama, a flat rectangle laid out before the viewer. The aim is to re-create the sensation of being confronted with a panoramic landscape: just as when faced with a landscape, what lies at the periphery of the view is blurred for the viewer / walker, here what lies at the periphery of the double-page spread is blurred.

gallery

The play with format is particularly prevalent in the conceptualisation of the photographs of the mountain pass Mám Éan (CE, pp.40 and 43), not least because Mám Éan has a specific significance in the Connemara trilogy, since it was here that the idea of Robinson’s project was envisaged. In ‘Mám Éan / the pass of birds’ (fig. 1), the view of the pass stretches to the north-east; in ‘ ‘usque ad ultimum terrae’ ‘ (fig. 2) the view stretches to the south-west. In order therefore to see the full panorama, it is necessary to hold the intervening page (CE, pp.41-2) vertically open. The page is thus held in a state of unstable equilibrium, reflecting the unstable equilibrium that Robinson talks of in the juxtaposed text, and the very act of reading becomes a ‘topographical sensation’. The interplay between viewing and reading, between landscape and page, is highlighted by the deliberate layout of the textual extracts concerning Mám Éan (p.42) in such a way as to reflect the contrasts of the opposite image, the topmost paragraph from My Time in Space reflecting the movement of the cloud and so on. Interrupting the standing landscape of the two photographs – particularly striking in what could be termed the standing layers of the mountain slopes thrown into relief in the image ‘Mám Éan / the pass of birds’ and typical of the Connemara landscape – is the flattened surface of the map (CE, p.41), pointing to a shift from the perpendicular viewpoint of the photographer to the bird’s eye view of the cartographer. The translation of the landscape to print is then highlighted in the adjoining page (CE, p.44), the final page in this little unit devoted to Mám Éan, where the page describing the origin of Connemara is superimposed on the map which represents its place of genesis. The viewpoint is now one of narrative. In short, in these pages, the physical act of reading is implicated and the gaze is dislocated.

3. ‘Echolalia’ / ‘The print of nature’

As is clear from the remarks above concerning the translation of the land on to the page, key to ‘Browsing Connemara’ is a questioning of our relationship with (the idea of) surfaces, and a questioning of the frequent representation of the earth as surface. Around these surfaces of text, image, map, the idea underpinning the essay is to re-introduce consideration of other dimensions, by folding and unfolding an anthology of surface-pages. Those dimensions are the depth added by the spine, and the blanks between texts and images. The pages of a book are never at the same place; the material object of the book always offers depth although only one surface is visible at a time. Furthermore, through the rhythm of turning the pages, a depth of time is added to these plane surfaces. (It is hardly surprising that it is a book about Connemara that lends itself to an investigation of surfaces, given the multiplicity of surfaces with depth which are scattered around its landscape and which scatter light around its landscape: strands, tides, roads, bogs, hills).

This investigation of surface underpins many of the photos, as is made explicit at times by the interplay between title and photograph (‘The depth of the surface’, ‘Plane surface’, ‘The depth of field’, ‘Still pane’, for example). It is particularly prevalent in the double-page spread featuring ‘Echolalia’ (fig. 3) and ‘The print of nature’ (fig. 4) (CE, pp.106-7). To come into being, photographs and text need to be printed on a surface; the surface is a place of apparition for them and for their referent. ‘The print of nature’ hinges explicitly on the direct contact between the object (here, the bog-cotton) and the sensitive surface. The direct placing of the bog-cotton on the photo-paper gives rise to a photogram. Resembling a lighting match, the over-exposition of the flower produces the impression that the flower is burning the page-surface. Given the nature of the image as a photogram and given the title, the image also suggests an allusion to the first photo-book, W. H. F. Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844-46). Similarly, ‘Echolalia’ – the title a nod to Denis Roche’s Photolalies (1988) – presents the image of a water-lily at the water’s surface, that surface thrown into relief by the reflections of the water around the flower. The stems of two leaves floating on the surface, descending into the water, points to the fact that the water-lily is a plant which feeds in the darkness of the pool but which flowers at the surface. By extension, the image is a representation of those pools of darkness which nourish the photographic process. In terms of layout, the step-like disposition of the photographs and the Robinson textual extracts here reproduces the schematic explanation of fractals, recalling Robinson’s diagrammatic drawing of the process of fractalization reproduced earlier (CE, p.68). Furthermore, the extensive use of blank space on these two pages is a nod to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry, particularly ‘Un coup de dés’ (1897), the first literary text to play extensively with layout and typography, and noteworthy for its use of blank space. The image of the water-lily also recalls Mallarmé’s ‘Le nénuphar blanc’ (‘The White Water-Lily’), and the use of the colour white in his writings. Finally, in an express reminder of how the turning of the pages of the book creates echoes, the image recalls the earlier photograph of a water-lily ‘Nymphaea alba’ (CE, p.62) which also plays with layout and blank space both internally and in its juxtaposition with the largely blank opposing page, a page which fittingly situates a comment from Tim Robinson concerning the primordial significance of blank space in cartography, where lies ‘our own imagined presence’. These blank spaces in ‘Browsing Connemara’, the ecotone of text and image, are the intervals for the interpreter, who is a key element for both photograph and landscape, both speechless.

4. 'Hexagon'

Hexagon

The triptych concerning Richard Murphy’s hexagonal Omey house (CE, pp.108-9) continues to play with the idea of surfaces and tries to give an example of how a place on the earth is showing forth (and hence of geophany). The same place can be seen to show itself differently to different people and at different moments. Juxtaposed with Robinson’s remarks concerning intertextuality and particularly the idea that the ‘fractal nature of intertextuality is the clue to the way the text itself sits into the fractals of non-textual reality’, the triptych creates an intertextuality where each of the images extends beyond its material limits. The first image is a photograph of a page from The Last Pool of Darkness where Robinson writes of the Omey ‘scriptorium’, drawing on Murphy’s memoir The Kick (2002) for its description. It is a graphic representation therefore of Murphy’s text within Robinson’s text. The second image is a photograph of the poem inspired by the hexagonal house, Murphy’s ‘Hexagon’, superimposed on the cartographic representation of the site of the same building. The visible creases of the map, together with the thickness of the poetry volume, add relief to the surface of the image. The third image is one of the hexagonal house itself (‘Hexagon’, fig. 5) in a visual representation which presents shot and counter-shot simultaneously. I am standing in front of the glass of the window, which reflects my shadow. On either side of and above my shadow, the landscape behind me is visible (the counter-shot) but it blurs with the inside of the house which is in front of me (the shot) – the hexagonal table, the sink and the window which is opposite the one at which I am standing. The window, given the light and thanks to my shadow, functions simultaneously as a mirror and as the transparent pane that it is, allowing both the inside of the house, and the landscape behind the house through the opposite window, to appear. The image represents three plane surfaces simultaneously, transcending the limits of a single surface, and in so doing reflects the ways in which the text and image relations of the triptych as a whole transcend the limits of a single surface. The out-of-field of the photograph ‘Hexagon’ is not only the rest of the land which we don’t see, the land beyond the edges of the photograph, but it is also the Richard Murphy poem, the Tim Robinson text. The aim of the montage is to call into question the traditional definition of landscape, which is revealed as truncated, abridged. It also reminds us that a landscape is a memory, often silent or forgotten, a deposit of materials from very diverse origins. How do we relate to the landscape, and how do we relate the landscape? From where is the landscape speaking? Tim Robinson says he is ‘writing blind’, and the photographer shows a blind ‘I’.

5. ‘Déjà vu’

Déjà vu’

The absence of perspective, in the traditional Albertian sense of the term, and the flatness or platitude I wanted to capture in these photographs, is highlighted in the image ‘Déjà vu’ (fig. 6). On one level, this image aims to represent the way in which Tim Robinson works and composes his books. The barbed wire catches the strands of sheep’s wool, just as Robinson’s writing catches different elements of the landscape, a creative process of reverie reflected in the title of the earlier ‘Wool gathering’ (CE, p.24). The wire threads together these disparate strands of wool of varying length, just as throughout his trilogy Robinson threads together the texts of varying length that he has noted down on returning from his walks. Aesthetically, stretching out over a grey flatness as it does, the photo demonstrates the diffuse and shadowless light typical of Connemara. Furthermore, on looking at the photo, the gaze follows the barbed wire from left to right, as it would a line of writing, in search of the point which is sharp. The accompanying text on the facing page also runs in full across the page (unlike many other pages in the book) in order to echo this movement. In the absence of perspective, the depth of field is reduced to a single segment of wool-covered wire. Yet the image is marked by a second opposing movement, from right to left, following the direction in which the wind blows the wool. This second movement slows down the gaze and brings it back to the left-hand page, the page of text. As the gaze returns to the photo, the image is therefore déjà vu – the ‘Déjà vu’ of the title – all the more so since the right-hand page is revealed first when one turns the page in the reading conventions of today’s Western culture, and triply déjà vu for the photographer. The title also provides a nod to the earlier ‘Wool gathering’, mentioned above, which makes this second image of wool-covered wire déjà vu by its position in the book. The photograph expands as a temporal material, in front of which one has to orientate oneself on the spot.

6. Conclusion

‘Browsing Connemara’ proposes a stroll through the landscape of Tim Robinson’s writing and cartography, and through the landscape of photography. Having walked the Connemara land, folded and unfolded Connemara, Connemara and Elsewhere tries to understand a place configured by light and words, by the imprint of time in a land and the imprint of place in time. In this perpendicular, even orthographic, walking of the land, the camera which ‘traces’ the landscape is limited by the shutter to outlining a frame and an out-of-field, in other words by the trace of an anachronistic present left on a piece of paper. This photographic translation of landscape to page layout can only take place within a poetics of vacancy, where the voice of the images can be heard, thanks to the mute function of photography, in other words, where the echo of the world is propagated. The ‘echosphere’ – another Tim Robinson neologism – tries to make the relations between an ‘I’ and nature resound. To sum up, the essay ‘Browsing Connemara’ aims to provide not only a visual representation of the landscape of Connemara, but equally a visual account of that landscape, particularly as it unfolds in a book. It aims to transfigure the landscape through a configuration of ‘the geophanic arts and sciences’ and thus to experience, as Robinson posits geophany should, a ‘means towards a reformation of values’.*

*Tim Robinson, ‘A land without shortcuts’, The Dublin Review, 46 (Spring 2012), 25-44 (p.44).